For Love of the Prequels

by Aster Gilbert

Hello there. Star Wars fans are known for their passionate loyalty to that galaxy far, far away. And nothing gets our blood pumping more than a good old-fashioned throw-down on the Prequel trilogy. For some, the Star Wars Prequels are the worst films ever made—simply saying “the Prequels” is a punchline in itself. But for others—such as yours truly—the Prequels are exhilarating adventures unlike any other blockbuster films. This divide, which seems to have no middle ground, is as fierce today as when The Phantom Menace was released in 1999. Red Letter Media’s savage take down of The Phantom Menace has over 9 million views on YouTube (warning: not safe for work-at-home). The justifications for Prequel hate have become pop culture canon: Jar Jar Binks, cheesy performances, Jar Jar Binks, and a failure to live up to the vaunted original trilogy. Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) changed American pop culture forever, and The Empire Strikes Back (1980) is, along with The Godfather Part II (1974), one of the few sequels considered to surpass its predecessor. But perhaps this is the problem that doomed the Prequels from the start: being measured against three of the most beloved films in American history.

Full disclosure: I’m an avid fan of the Prequel trilogy. But I’m not unreasonable. Jar Jar is, uh, a bit much and Anakin’s infamous “I hate sand” monologue from Attack of the Clones (2002) is pretty goofy. But to love Star Wars is to embrace the silliness along with the grandiosity. This has always been the secret sauce to George Lucas’ genius: building a world overflowing with variety. Lucas’ galaxy far, far away is filled with mysticism, adventure, romance, slap-stick, and plenty of whimsy. It’s an epic space opera tragedy of betrayal and loss, populated by rogues, wretches, and jesters. And the Prequels are the ultimate achievement of Lucas’ life-long fascination with pulp adventure serials. The original Star Wars (1977) was born out of Lucas’ failure to acquire the rights to make a Flash Gordon movie. So, he created his own galactic adventure, reworking plotlines and characters from both Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers serials of the 1930s. Lucas perfectly emulated their style: cardboard sets, space ship models on strings, beleaguered princesses, and evil space empires. Lucas brought all of this to Star Wars (1977), along with some wooden acting and dopey dialogue, that was held together by genuine conviction and the thrill of a great cinematic adventure. From the famous opening crawl, Star Wars (1977) hit the ground running and it never stopped moving until the end credits. If it did, you’d notice the seams and duct tape holding it all together.

It’s these same principles that make the Prequel trilogy so great. The Prequels accelerate this non-stop serial adventure movement. What Lucas does, is take an entire 12-part Buck Rogers adventure and condenses it into a single feature film. It’s not that Lucas doesn’t grasp the classical three-act structure, but rather he’s doing something else entirely! The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith (2005), can each be thought of as entire serials in-and-of themselves. And like binge-watching an old serial, they twist and turn through different genres and styles. Attack of the Clones is a perfect example: constantly mutating from political intrigue, buddy-cop chases, romance, and a noir-inflected detective plot, culminating in a 1930s John Carter of Mars monster battle only to segue right into a war movie. As the dense plot is constantly unfurling, the political terrain keeps shifting, and this kaleidoscope of pulpy genres keeps on spinning. It’s this sense of constant movement that transforms the Prequels from simply filling in the blanks of what happened before Star Wars (1977) into a strange and unique experience unlike anything before or since.

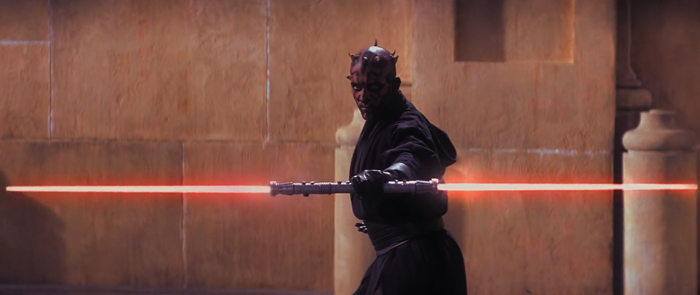

The non-stop momentum of the Prequels is not just the result of new green screen computer technologies, but perfectly expresses Lucas’ idea of the Star Wars universe. The Jedi versus Sith is more than good versus evil; it’s about competing philosophies of life, death, and power. The Phantom Menace introduces these themes immediately. The Jedi preach a philosophy of Zen-like mindfulness; to be attuned to the present moment instead of anxious about the future. But the Sith are always scheming in the present to design the future and cheat death. Master Qui-Gon instructs Obi-Wan to cultivate stillness in order to better respond to what’s happening in the now. And while this serves them well in the short term, surviving attacks and saving the Queen, it makes them vulnerable to the far-reaching plans of the puppet-master behind the curtain. The Phantom Menace is filled with rapid sequences that cut between movement and stillness. Take for example the opening cross-cuts between the mindful Jedi and the scheming Sith, which opens the Prequel trilogy with tension and duplicity. Better yet, consider the breathtaking podrace sequence. Now, I’ve often heard detractors say that the podrace was pointless. But alas! Lucas uses the kinetic action of a race to provide a vehicle for the film’s ideas. Qui-Gon trains young Anakin in the ways of the Jedi, to be mindful of the moment while screaming forward at break-neck speed. This sequence serves to represent the entire Prequel trilogy: how to be attuned to the moment when things are changing faster than you can comprehend?

But the Prequels aren’t simply a distracting soup of genres or fast and punchy action. The films are cleverly plotted and structured. Everything that happens is the result of Palpatine’s schemes and the heroes are always a few steps behind. It’s like watching flies navigate a spider’s web. For all the philosophical benefits, Jedi mindfulness also makes the heroes a constant target to a well-organized and patient enemy. Here, Lucas not only draws from classic space opera, but the silent film crime serial. Like Louis Feuillade’s cunning Fantômas always outwitting inspector Juve (1913) and Fritz Lang’s Mabuse, ensnaring everyone in his global empire of crime (1922, 1933, 1960), Lucas pits the detail-oriented criminal masterminds against a vulnerable organic human goodness. The Prequel trilogy are films about mysteries that we already know the answers to. We know Anakin becomes Darth Vader. We know Vader destroys the Jedi. We know Darth Sidious is Palpatine. It’s all in the panache and showmanship of spinning that yarn.

What makes these evil schemes so juicy, is that Lucas portrays the Jedi as figures of colossal hubris. In their short-sightedness they co-author their own downfall. Everything in the Prequels orbits the themes of Jedi arrogance. The arch-tragedy of Anakin’s seduction into Darth Vader is paved by the out-of-touch smugness of Yoda, Windu, and even Obi-Wan. They at first refuse to train Anakin, they don’t take him seriously, and they dismiss his concern for his mother, all of which are exploited by Palpatine. In the decades between the original trilogy and the prequels Lucas could have envisioned a number of ways that the noble Jedi order fell and Palpatine became the evil emperor. He could have relied on superweapons or invasions. Instead, he wove a tapestry of deception and arrogance within a dense moral fog that oppresses the clear vision of the young.

The Jedi are convinced by an illusion of certainty in ever-changing circumstances. Take for example the structure of Attack of the Clones. Throughout the film, the young heroes Obi-Wan, Padme, and Anakin, are always right in their assessment of the situation. After the tragic assassination that opens Clones, Padme correctly identifies Count Dooku as the culprit, which the Jedi council dismisses entirely. After the council gives Anakin his first solo mission, Obi-Wan rightfully objects that Anakin is not ready. “The council is confident in its decision” Master Yoda replies. Again and again the truth of the young is ignored, to tragic results. This arrogance is anticipated by Palpatine, who exploits the doubt, frustration, and short sightedness of the heroes.

And so, these are just some of the reasons that I have come to love the Prequel trilogy. I watch them frequently—more frequently than I think my wife would like. It may simply be a matter of taste depending on your tolerance for wonky pulp serials. And that’s totally fine, to each their own Star Wars!

Lastly, if I’ve failed to seduce you to the dark side of Prequel love, then allow me to leave you with this: The Clone Wars. If anything can bridge the divide between Prequel lovers and haters, it’s the The Clone Wars TV series. Sporting a brilliantly simple style, compelling characters, and morally complex plot lines, the animated Clone Wars is Star Wars at its pulpy best. There are even two flavors to choose from! Star Wars: Clone Wars (2003-2005) was first a traditionally animated Cartoon Network series by famed animator Genndy Tartakovsky (of Samurai Jack and Hotel Transylvania fame). It’s wild animation style and micro-episode format makes for some of the weirdest stuff in the Star Wars universe. And second, the computer animated series The Clone Wars (2008-2020) has taken on a life of its own as one of the most beloved entries in the Star Wars canon. These cartoons are comparable in quality to the iconic Batman The Animated Series (1992-1995): a Saturday morning cartoon that had no business being more sophisticated than most blockbuster movies! The comparison is apt, given that many Batman The Animated Series alums went on to work on both versions of The Clone Wars. If you’ve never given the cartoons a chance, what better time than now to dive in! And may the force be with you.

Aster is the GenreQueer Coordinator at Milwaukee Film.

Posted by: Tom Fuchs